Deep Compression for Improved Inference Efficiency, Mobile Applications, and Regularization

As technology cozies up to the physical limits of Moore's law, computation is increasingly limited by heat dissipation rather than the number of transistors that can be packed onto a given area of silicon. Modern chips already routinely idle whole sections of their area forming what's referred to as "dark silicon," referring to design constraining the proportion of the chip that can be powered on for extended periods of time before dangerously surpassing thermal design limits. An important metric for any machine learning accelerator, including tried and true general purpose graphics processing units (GPUs), is therefore the training or inference performance of the device at about 250 W of power consumption.

It's this drive for efficiency that prompted Google to develop their own tensor processing unit (TPU) in-house for increasing the efficiency of model inference, as well as training in the v2 unit onward, in their data centers. The last few years have seen a plethora of deep learning hardware startups that seek to produce energy-efficient deep learning chips that specialize in the limited mix of operations required for currently fashionable deep learning architectures. If deep learning mostly consists of matrix multiplies and convolutions, why not build a chip that does just that, trading general computing capabilities for specialized efficiency? But there's more to this tradeoff then meets the eye.

The Energy Cost of Deep Learning

The main power sink in modern high performance computing including machine learning at scale isn't computation, it's communication. Performing a multiply operation on 32 bits of data typically requires less than 4 pJ, while fetching that same amount of data from DRAM requires about 640 pJ, making off-chip memory reads about 160 times more energy-expensive than commonly used mathematical operators. That lopsided power consumption gets even worse when we consider sending data more than a few centimeters (leading data-centers to replace mid-length data communication wires with optical fibers). Suddenly outsourcing your deep learning inference requirements to run on Google Cloud Platform's TPUs doesn't seem as green as it could be.

It almost goes without saying that given the pace of innovation in artificial intelligence and machine learning, there's no guarantee that the dominant architectures will remain unchanged long enough to fully reap the rewards after investing a 2 year development cycle for specialized hardware that is restricted to high-performance on convolutions and matrix multiplies. Just in the last few months we've seen demonstration of promising Neural Differential Equation networks, which operate quite differently than our much-revered conv-nets, and the increased interest in deep learning this decade can only mean more innovation and new types of models. Any specialized hardware developed specifically to accelerate the current generation of top models runs the risk of rapid obsolescence.

Deep Compression: Biologically Inspired Efficiency Improvements

Deep learning convolutional neural networks, as their name suggests, are known for their depth and width, with some exceptional examples of resnets having about 1000 layers. At the end of training all that precision in all those parameters can be overkill, little more than wasted computational resources with a ravenous appetite for electricity. That's a major reason behind Nvidia's variable precision tensor cores with support for computations all the way down to 8-bit integers in the latest generation Turing architecture GPUs.

Achieving state-of-the-art performance with smaller models (like the aptly named SqueezeNet), is therefore an active area of research. Fully trained, smaller models are ideally suited for mobile deployment in autonomous cars, internet-of-things devices, and smart phones, but training is still most effective when the parameter search is large. Luckily there's a biological analogue in the way human brains develop. Using synaptic pruning, the human brain becomes more efficient as people progress from childhood into adulthood. It's this feature of mammalian neurological development that inspired a set of compression techniques for deep learning models.

Estimates of the maximum number of synapses present during early childhood development range upward to as many as 1000 trillion, but after synaptic pruning these decrease about 10X to around 100 trillion in adults. Not only does this decrease the metabolic demands of the tissue, but facilitates learning a more complex structural understanding of the world. In deep learning as well, pruning weights has its origins as a regularization technique for improving model generalization, before the advent of widespread training on GPUs. Combining parameter pruning, parameter quantization, and parameter coding in a model compression and optimization process known as Deep Compression won Song Han et al. the ICLR best paper award in 2016. Not only does deep compression result in model sizes that are 35-50 times smaller, run faster, and require less energy (great for deployment in battery-powered applications), but the models often achieve better performance than the original, uncompressed model.

Dense-Sparse-Dense Training

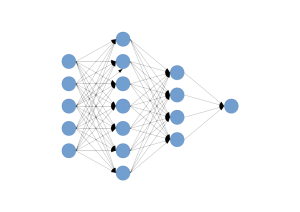

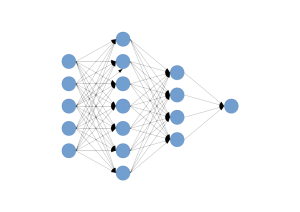

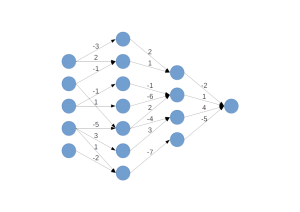

Much like the mutable mind of a newborn babe, a typical multilayer perceptron architecture features dense interconnections between neurons such as shown in the cartoon below:

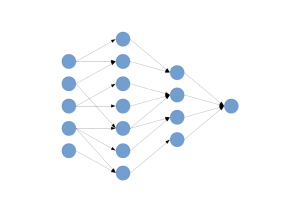

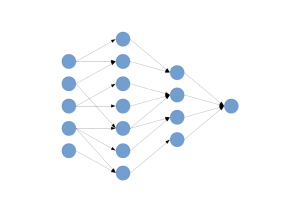

After training, if we were to probe the parameter values defining each weighted connection, we'd discover two important characteristics. First, many of the weight values are very close to zero, so we should be able to discard them without significantly effecting the overall performance of the network. Second, much of the information represented by the weights is in fact redundant. Discarding near-trivial weights and retraining the network over several iterations reduces redundancy in what the network learns, much like the elegantly effective dropout regularization technique. Iteratively pruning and re-training the model in what's called dense-sparse-dense training can remove up to 90% of parameters with no loss in test accuracy (PDF).

Parameter Quantization

A 90% reduction in parameters is pretty good, but at this point there is still ample opportunity to optimize the model, which may still be too large to squeeze into on-chip SRAM. During training we would typically be using high precision data types, such as 64-bit floats, but at the end of the day we'll usually find that whether a weight's value is plus or minus 1e-33 is probably not going to make much of a difference at test time. By quantizing the remaining parameters, we can take advantage of efficiency and speedup from features such as Nvidia's INT8 inference precision and further reduce the model size. If we're deploying over-the-air updates to autonomous vehicles or IoT devices smaller model sizes equate to savings on communication costs and time for both our customers and ourselves, while avoiding some of the pitfalls of off-device cloud compute for routine features.

Huffman Coding (Extra Credit)

Stopping after dense-sparse-dense training and parameter quantization is already enough to reduce storage requirements for the iconic AlexNet by more than 26 times without any significant loss of performance. There is one more step to achieving the full depth of benefits from deep compression, and that's weight sharing. You'll recall that we already benefit from significant weight sharing benefits in moving from fully connected to convolutional neural network architectures, as each weight in each convolutional kernel is applied as a sliding window across the entire preceding layer. This decreases the total number of parameters in a given model by orders of magnitude next to a comparable densely connected multi-layer perceptron. But we can achieve further weight sharing benefits by applying k-means clustering to the population of weights, using the centroid value as the parameter value for each group and placing these values in a lookup table.

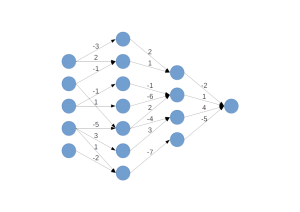

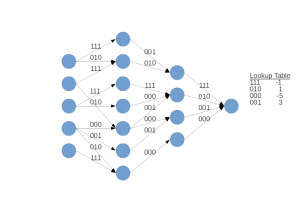

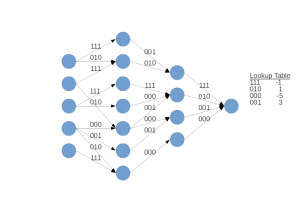

In cartoon form, this concept looks something like this:

Conclusions

Deep compression is one way to encourage your deep learning models to work smarter, not harder, and enables improvements in energy efficiency, inference speed, and mobile deployment. Furthermore, training big models on flexible general purpose GPUs and later compressing them for inference and deployment combines some of the best capabilities of deep and broad models, mainly casting a wide net in parameter search during the learning process, with the ability to deploy a much smaller finished model for on-device deployment. On-device machine learning enhances privacy and offers improved reliability for essential features for applications like autonomous driving. Model optimization techniques like deep compression shrink the moats surrounding tech giants with the resources to hire teams of semiconductor engineers to develop in-house machine learning hardware, and reduces reliance on running big models on cloud services.

Deep Compression: Optimization Techniques for Inference & Efficiency

Deep Compression for Improved Inference Efficiency, Mobile Applications, and Regularization

As technology cozies up to the physical limits of Moore's law, computation is increasingly limited by heat dissipation rather than the number of transistors that can be packed onto a given area of silicon. Modern chips already routinely idle whole sections of their area forming what's referred to as "dark silicon," referring to design constraining the proportion of the chip that can be powered on for extended periods of time before dangerously surpassing thermal design limits. An important metric for any machine learning accelerator, including tried and true general purpose graphics processing units (GPUs), is therefore the training or inference performance of the device at about 250 W of power consumption.

It's this drive for efficiency that prompted Google to develop their own tensor processing unit (TPU) in-house for increasing the efficiency of model inference, as well as training in the v2 unit onward, in their data centers. The last few years have seen a plethora of deep learning hardware startups that seek to produce energy-efficient deep learning chips that specialize in the limited mix of operations required for currently fashionable deep learning architectures. If deep learning mostly consists of matrix multiplies and convolutions, why not build a chip that does just that, trading general computing capabilities for specialized efficiency? But there's more to this tradeoff then meets the eye.

The Energy Cost of Deep Learning

The main power sink in modern high performance computing including machine learning at scale isn't computation, it's communication. Performing a multiply operation on 32 bits of data typically requires less than 4 pJ, while fetching that same amount of data from DRAM requires about 640 pJ, making off-chip memory reads about 160 times more energy-expensive than commonly used mathematical operators. That lopsided power consumption gets even worse when we consider sending data more than a few centimeters (leading data-centers to replace mid-length data communication wires with optical fibers). Suddenly outsourcing your deep learning inference requirements to run on Google Cloud Platform's TPUs doesn't seem as green as it could be.

It almost goes without saying that given the pace of innovation in artificial intelligence and machine learning, there's no guarantee that the dominant architectures will remain unchanged long enough to fully reap the rewards after investing a 2 year development cycle for specialized hardware that is restricted to high-performance on convolutions and matrix multiplies. Just in the last few months we've seen demonstration of promising Neural Differential Equation networks, which operate quite differently than our much-revered conv-nets, and the increased interest in deep learning this decade can only mean more innovation and new types of models. Any specialized hardware developed specifically to accelerate the current generation of top models runs the risk of rapid obsolescence.

Deep Compression: Biologically Inspired Efficiency Improvements

Deep learning convolutional neural networks, as their name suggests, are known for their depth and width, with some exceptional examples of resnets having about 1000 layers. At the end of training all that precision in all those parameters can be overkill, little more than wasted computational resources with a ravenous appetite for electricity. That's a major reason behind Nvidia's variable precision tensor cores with support for computations all the way down to 8-bit integers in the latest generation Turing architecture GPUs.

Achieving state-of-the-art performance with smaller models (like the aptly named SqueezeNet), is therefore an active area of research. Fully trained, smaller models are ideally suited for mobile deployment in autonomous cars, internet-of-things devices, and smart phones, but training is still most effective when the parameter search is large. Luckily there's a biological analogue in the way human brains develop. Using synaptic pruning, the human brain becomes more efficient as people progress from childhood into adulthood. It's this feature of mammalian neurological development that inspired a set of compression techniques for deep learning models.

Estimates of the maximum number of synapses present during early childhood development range upward to as many as 1000 trillion, but after synaptic pruning these decrease about 10X to around 100 trillion in adults. Not only does this decrease the metabolic demands of the tissue, but facilitates learning a more complex structural understanding of the world. In deep learning as well, pruning weights has its origins as a regularization technique for improving model generalization, before the advent of widespread training on GPUs. Combining parameter pruning, parameter quantization, and parameter coding in a model compression and optimization process known as Deep Compression won Song Han et al. the ICLR best paper award in 2016. Not only does deep compression result in model sizes that are 35-50 times smaller, run faster, and require less energy (great for deployment in battery-powered applications), but the models often achieve better performance than the original, uncompressed model.

Dense-Sparse-Dense Training

Much like the mutable mind of a newborn babe, a typical multilayer perceptron architecture features dense interconnections between neurons such as shown in the cartoon below:

After training, if we were to probe the parameter values defining each weighted connection, we'd discover two important characteristics. First, many of the weight values are very close to zero, so we should be able to discard them without significantly effecting the overall performance of the network. Second, much of the information represented by the weights is in fact redundant. Discarding near-trivial weights and retraining the network over several iterations reduces redundancy in what the network learns, much like the elegantly effective dropout regularization technique. Iteratively pruning and re-training the model in what's called dense-sparse-dense training can remove up to 90% of parameters with no loss in test accuracy (PDF).

Parameter Quantization

A 90% reduction in parameters is pretty good, but at this point there is still ample opportunity to optimize the model, which may still be too large to squeeze into on-chip SRAM. During training we would typically be using high precision data types, such as 64-bit floats, but at the end of the day we'll usually find that whether a weight's value is plus or minus 1e-33 is probably not going to make much of a difference at test time. By quantizing the remaining parameters, we can take advantage of efficiency and speedup from features such as Nvidia's INT8 inference precision and further reduce the model size. If we're deploying over-the-air updates to autonomous vehicles or IoT devices smaller model sizes equate to savings on communication costs and time for both our customers and ourselves, while avoiding some of the pitfalls of off-device cloud compute for routine features.

Huffman Coding (Extra Credit)

Stopping after dense-sparse-dense training and parameter quantization is already enough to reduce storage requirements for the iconic AlexNet by more than 26 times without any significant loss of performance. There is one more step to achieving the full depth of benefits from deep compression, and that's weight sharing. You'll recall that we already benefit from significant weight sharing benefits in moving from fully connected to convolutional neural network architectures, as each weight in each convolutional kernel is applied as a sliding window across the entire preceding layer. This decreases the total number of parameters in a given model by orders of magnitude next to a comparable densely connected multi-layer perceptron. But we can achieve further weight sharing benefits by applying k-means clustering to the population of weights, using the centroid value as the parameter value for each group and placing these values in a lookup table.

In cartoon form, this concept looks something like this:

Conclusions

Deep compression is one way to encourage your deep learning models to work smarter, not harder, and enables improvements in energy efficiency, inference speed, and mobile deployment. Furthermore, training big models on flexible general purpose GPUs and later compressing them for inference and deployment combines some of the best capabilities of deep and broad models, mainly casting a wide net in parameter search during the learning process, with the ability to deploy a much smaller finished model for on-device deployment. On-device machine learning enhances privacy and offers improved reliability for essential features for applications like autonomous driving. Model optimization techniques like deep compression shrink the moats surrounding tech giants with the resources to hire teams of semiconductor engineers to develop in-house machine learning hardware, and reduces reliance on running big models on cloud services.