At last year's Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction competition (CASP13), researchers from DeepMind made headlines by taking the top position in the free modeling category by a considerable margin, essentially doubling the rate of progress in CASP predictions of recent competitions. This is impressive, and a surprising result in the same vein as if a molecular biology lab with no previous involvement in deep learning were to solidly trounce experienced practitioners at modern machine learning benchmarks.

The Protein Structure Prediction Problem

The machines of biology are encoded as sequences of information. The so-called central dogma of molecular biology posits that DNA sequences determine RNA sequences, which in turn determine the protein sequences and therefore structures as they fold into the biological nanomachines that give rise to biological traits. It's the last step we are concerned with in this post: predicting the 3-dimensional structure of proteins, which in turn form the building blocks for the mechanics of life.

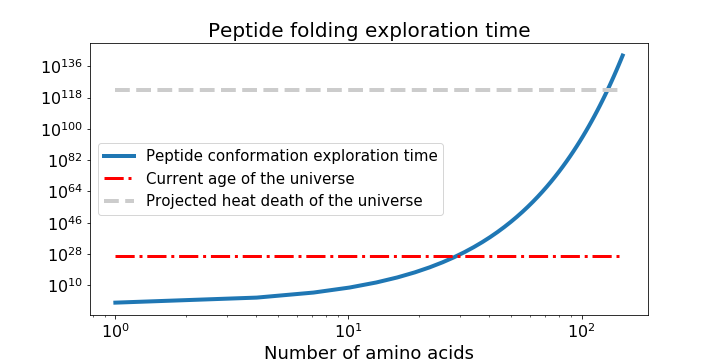

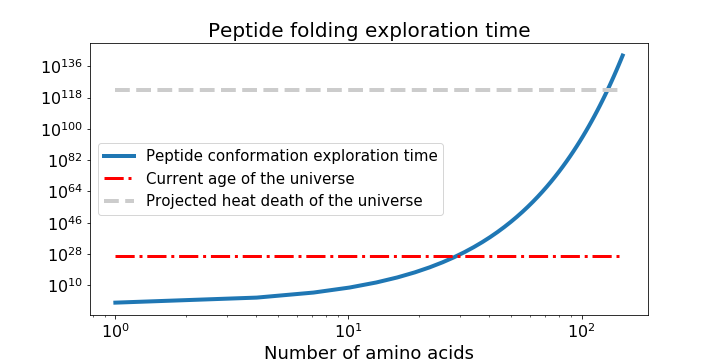

Imagine seeing an origami crane for the first time and trying to reverse-engineer the folds used to make it, when you've been given nothing but the unfolded piece of paper covered in hints written as parables from a foreign language. Now imagine that this reverse engineering problem meant folding the crane out of 1D strings instead of 2D sheets, and that it was in fact a real bird. This should give you an idea of the difficulty of protein structure prediction. Consider a short polypeptide chain where the links between each of 100 amino acids can adopt just three values of two angles. Spending 1 nanosecond per each possible conformation of the resulting peptide structure would take longer than the age of the universe by several orders of magnitude, a thought-experiment known as Levinthal's paradox.

Graph of protein folding time to explore peptide structure exploration time given two degrees of freedom and 3 possible positions for each peptide bond, and assuming 1 nanosecond spent to sample each conformation.

Protein structure prediction is a hard problem, but the potential impacts are huge. Proteins are the seat of structure and motor function in the cell, as well as signal carriers and enzymatic orchestrators of the complex biochemistry of life. Protein enzymes, for example, coordinate chemical reactions at the molecular scale in nano-scale pockets called active sites. Accurately predicting the structure of an active site and how it can be affected by mutations and small molecules can better inform both drug discovery and protein therapy. For a high-profile example, let's look at Cas9, the active protein used to clip DNA in CRISPR gene editing. The 2012 demonstration of CRISPR/Cas9 as a genetic tool promised to open our biological source code, but its potential is limited by a lack of targeting specificity, as using Cas9 runs an increased risk of causing mutations in un-targeted strands of DNA. Understanding the structure of Cas9 is a vital part of engineering CRISPR/Cas9-based gene-editing systems to have better specificity.

Cas9 protein (gray) in complex with guide RNA (red) and target DNA (orange). Protein Data Bank protein structure4008

Determining the structure of a given protein is a resource and time intensive process with plenty of room for trial and error, and the vast majority of known proteins don't have a known structure. While the number of protein sequences is following an exponential trajectory similar to other data-centric fields, the number of known protein structures is increasing at a much more incremental rate.

DeepMind's Approach to Protein Folding

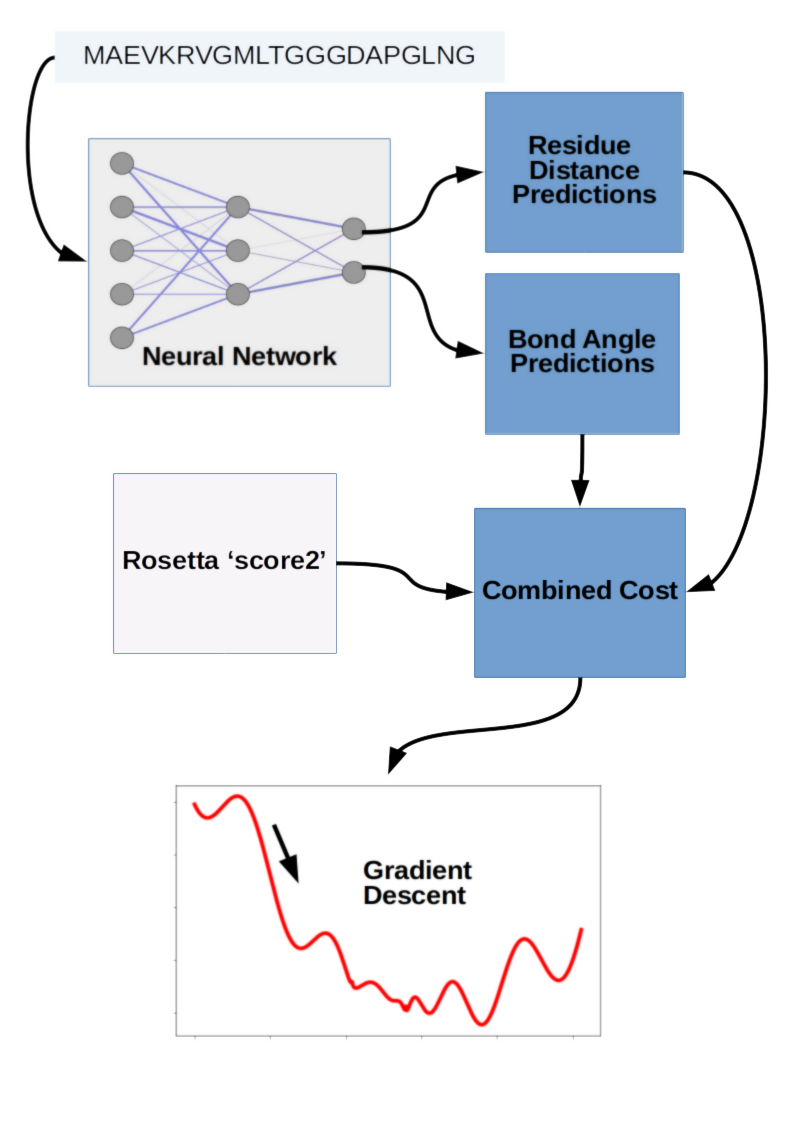

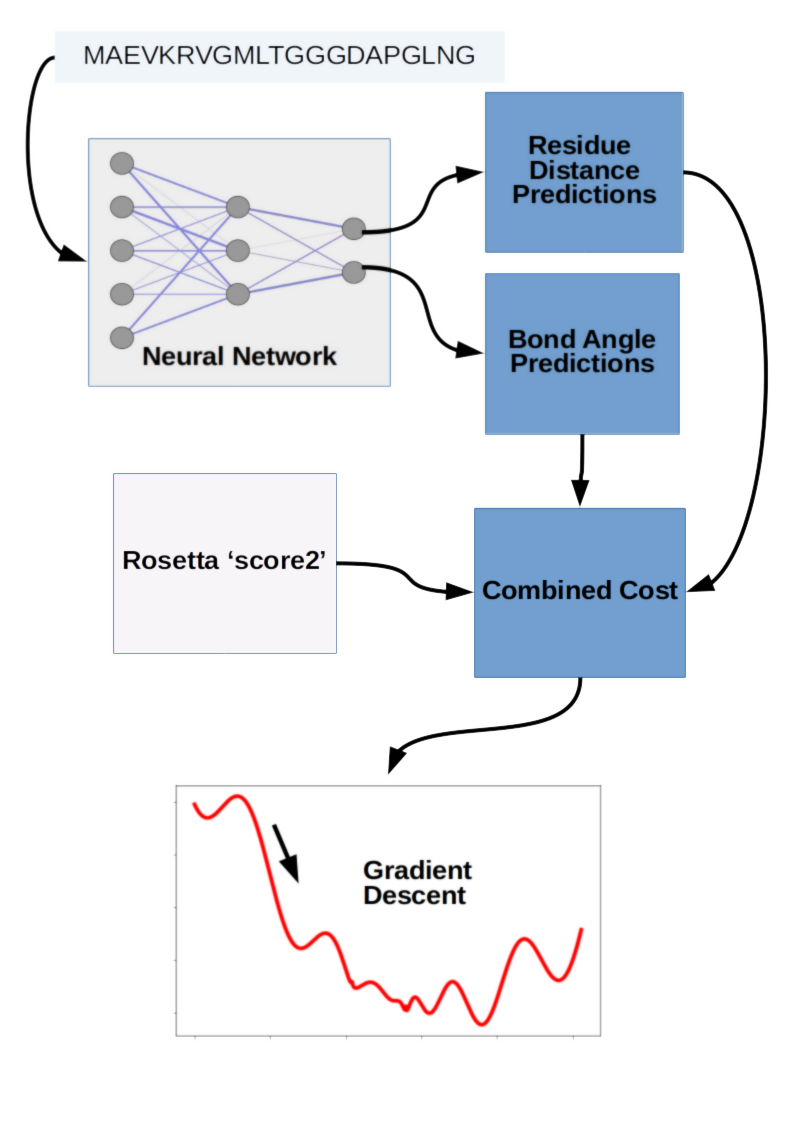

Coming from DeepMind, we might expect a massive end-to-end deep learning model for protein structure prediction, but we'd be wrong. Deep learning was just one aspect of the structure prediction process, and the final structures were actually a result of gradient descent optimization. The DeepMind team tried a 'fancier' strategy involving fragment assembly using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), but in the end the best results were obtained by gradient descent optimization. Gradient descent was applied to a combination of scores from their deep learning model as well as molecular modeling software Rosetta. The fragment assembly method and gradient descent method are referred to as method 1 and method 2, respectively, in the abstract.

Method 1: Fragment Assembly

The overall protein structure of a protein is a combination of smaller fragmented units of structure; these sub-units are somewhat modular and form motifs that are re-used with slight modifications across different proteins and protein families. This is a major reason for the use of multiple sequence alignment as part of most protein structure prediction models. By comparing a novel protein sequence to a database of sequences that have known structures, an estimate of the sub-structure in the new protein can be inferred by taking the structures formed in proteins with similar sequences as templates.

Notably, while DeepMind did use multiple sequence alignment in their approach, they did not use any templates. That is, while they did compare the sequences to databases of known protein fragment sequences, they didn't borrow structures associated with those sequences directly. They used a generative neural network to come up with fragment candidates for insertion into an otherwise more conventional structure optimization workflow using simulated annealing. Although GANs have matured substantially in the past few years with impressive results on tasks like de novo image generation, in this case the results were not state of the art. For that DeepMind would combine old and new with a pipeline incorporating deep learning for scoring and gradient descent for objective optimization.

Method 2: Gradient Descent on Deep Learning Scores

The core deep learning aspect of DeepMind's winning entry was a neural network that predicted likely distances between amino acid pairs, as well as the angles of each peptide bond linking amino acid residues. These two predictions were then incorporated into a score along with 'score2' from Rosetta modeling software, followed by gradient descent to minimize the combined objective cost directly. This is a bit of an unfair simplification of all the engineering work that went into making the process work so well, but conceptually the winning prediction strategy was surprisingly simple. It wasn't an end-to-end deep learning project, and the fancier method involving GANs didn't perform as well. Taken together the DeepMind entry suggests that clever strategy can still beat brute force computational resources applied with big deep learning models, and emphasizes the need to maintain some flexibility in your machine learning hardware and software stack. This is somewhat in contrast to the approach espoused by OpenAI, where they have published impressive results in >game-playing, text generation, and music synthesis using essentially the same Long Short-Term Memory model.

What's Next?

As we mentioned above, DeepMind's entry to CASP13 was an upward departure from the rate-of-progress of previous CASP competitions, and they beat the field by a substantial amount. Thanks to their solid and surprising performance and high-profile press coverage, we might be concerned that the problem is solved and protein folding bioinformaticists are out of a job. Some statements may be further from the truth, but the reality is that even if progress continues at at the new pace set by AlphaFold, it will take about 4 years or so for protein structure prediction to reliably achieve 85% gross topology or better on arbitrary protein sequences.

End-to-end differentiable models and those that predict protein structure directly did significantly worse than AlphaFold on CASP13. One of the challenges unique to the protein sequence prediction field is that the rate of data generation is slow compared to that in other fields. That's a roadblock to seeing the deep learning breakthroughs we've seen in other fields with massive datasets. New protein sequences, on the other hand, continue to be added to databases like UniParc at an exponential pace. We've seen what unsupervised learning can do for other sequence to sequence domains like text, and promising results from unsupervised learning of protein sequences. Combining deep predictive knowledge of protein sequences with advances like we've seen with AlphaFold is a promising and under-explored area of future research.

In this article we talked about the challenges inherent to the static folded protein problem of sequence-to-structure prediction, but there's also the dynamic protein folding problem, which is to understand the process of folding itself. Solving the former will give us vital insights into biology, actionable as improvements in biotechnology and medicine via better drug discovery and protein engineering. Solving the latter problem will add another order of difficulty as well as an order of benefit. Understanding the protein folding process will help us to understand why good proteins go bad, as they do in so many modern diseases such as those that cause dementia. This is also a very promising area for data-oriented researchers looking for a field full of unsolved problems where they can make substantial contributions with a real impact.

Other Deep Learning + Molecular Dynamics Blogs you may be interested in

A Summary of DeepMind's Protein Folding Upset at CASP13

At last year's Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction competition (CASP13), researchers from DeepMind made headlines by taking the top position in the free modeling category by a considerable margin, essentially doubling the rate of progress in CASP predictions of recent competitions. This is impressive, and a surprising result in the same vein as if a molecular biology lab with no previous involvement in deep learning were to solidly trounce experienced practitioners at modern machine learning benchmarks.

The Protein Structure Prediction Problem

The machines of biology are encoded as sequences of information. The so-called central dogma of molecular biology posits that DNA sequences determine RNA sequences, which in turn determine the protein sequences and therefore structures as they fold into the biological nanomachines that give rise to biological traits. It's the last step we are concerned with in this post: predicting the 3-dimensional structure of proteins, which in turn form the building blocks for the mechanics of life.

Imagine seeing an origami crane for the first time and trying to reverse-engineer the folds used to make it, when you've been given nothing but the unfolded piece of paper covered in hints written as parables from a foreign language. Now imagine that this reverse engineering problem meant folding the crane out of 1D strings instead of 2D sheets, and that it was in fact a real bird. This should give you an idea of the difficulty of protein structure prediction. Consider a short polypeptide chain where the links between each of 100 amino acids can adopt just three values of two angles. Spending 1 nanosecond per each possible conformation of the resulting peptide structure would take longer than the age of the universe by several orders of magnitude, a thought-experiment known as Levinthal's paradox.

Graph of protein folding time to explore peptide structure exploration time given two degrees of freedom and 3 possible positions for each peptide bond, and assuming 1 nanosecond spent to sample each conformation.

Protein structure prediction is a hard problem, but the potential impacts are huge. Proteins are the seat of structure and motor function in the cell, as well as signal carriers and enzymatic orchestrators of the complex biochemistry of life. Protein enzymes, for example, coordinate chemical reactions at the molecular scale in nano-scale pockets called active sites. Accurately predicting the structure of an active site and how it can be affected by mutations and small molecules can better inform both drug discovery and protein therapy. For a high-profile example, let's look at Cas9, the active protein used to clip DNA in CRISPR gene editing. The 2012 demonstration of CRISPR/Cas9 as a genetic tool promised to open our biological source code, but its potential is limited by a lack of targeting specificity, as using Cas9 runs an increased risk of causing mutations in un-targeted strands of DNA. Understanding the structure of Cas9 is a vital part of engineering CRISPR/Cas9-based gene-editing systems to have better specificity.

Cas9 protein (gray) in complex with guide RNA (red) and target DNA (orange). Protein Data Bank protein structure4008

Determining the structure of a given protein is a resource and time intensive process with plenty of room for trial and error, and the vast majority of known proteins don't have a known structure. While the number of protein sequences is following an exponential trajectory similar to other data-centric fields, the number of known protein structures is increasing at a much more incremental rate.

DeepMind's Approach to Protein Folding

Coming from DeepMind, we might expect a massive end-to-end deep learning model for protein structure prediction, but we'd be wrong. Deep learning was just one aspect of the structure prediction process, and the final structures were actually a result of gradient descent optimization. The DeepMind team tried a 'fancier' strategy involving fragment assembly using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), but in the end the best results were obtained by gradient descent optimization. Gradient descent was applied to a combination of scores from their deep learning model as well as molecular modeling software Rosetta. The fragment assembly method and gradient descent method are referred to as method 1 and method 2, respectively, in the abstract.

Method 1: Fragment Assembly

The overall protein structure of a protein is a combination of smaller fragmented units of structure; these sub-units are somewhat modular and form motifs that are re-used with slight modifications across different proteins and protein families. This is a major reason for the use of multiple sequence alignment as part of most protein structure prediction models. By comparing a novel protein sequence to a database of sequences that have known structures, an estimate of the sub-structure in the new protein can be inferred by taking the structures formed in proteins with similar sequences as templates.

Notably, while DeepMind did use multiple sequence alignment in their approach, they did not use any templates. That is, while they did compare the sequences to databases of known protein fragment sequences, they didn't borrow structures associated with those sequences directly. They used a generative neural network to come up with fragment candidates for insertion into an otherwise more conventional structure optimization workflow using simulated annealing. Although GANs have matured substantially in the past few years with impressive results on tasks like de novo image generation, in this case the results were not state of the art. For that DeepMind would combine old and new with a pipeline incorporating deep learning for scoring and gradient descent for objective optimization.

Method 2: Gradient Descent on Deep Learning Scores

The core deep learning aspect of DeepMind's winning entry was a neural network that predicted likely distances between amino acid pairs, as well as the angles of each peptide bond linking amino acid residues. These two predictions were then incorporated into a score along with 'score2' from Rosetta modeling software, followed by gradient descent to minimize the combined objective cost directly. This is a bit of an unfair simplification of all the engineering work that went into making the process work so well, but conceptually the winning prediction strategy was surprisingly simple. It wasn't an end-to-end deep learning project, and the fancier method involving GANs didn't perform as well. Taken together the DeepMind entry suggests that clever strategy can still beat brute force computational resources applied with big deep learning models, and emphasizes the need to maintain some flexibility in your machine learning hardware and software stack. This is somewhat in contrast to the approach espoused by OpenAI, where they have published impressive results in >game-playing, text generation, and music synthesis using essentially the same Long Short-Term Memory model.

What's Next?

As we mentioned above, DeepMind's entry to CASP13 was an upward departure from the rate-of-progress of previous CASP competitions, and they beat the field by a substantial amount. Thanks to their solid and surprising performance and high-profile press coverage, we might be concerned that the problem is solved and protein folding bioinformaticists are out of a job. Some statements may be further from the truth, but the reality is that even if progress continues at at the new pace set by AlphaFold, it will take about 4 years or so for protein structure prediction to reliably achieve 85% gross topology or better on arbitrary protein sequences.

End-to-end differentiable models and those that predict protein structure directly did significantly worse than AlphaFold on CASP13. One of the challenges unique to the protein sequence prediction field is that the rate of data generation is slow compared to that in other fields. That's a roadblock to seeing the deep learning breakthroughs we've seen in other fields with massive datasets. New protein sequences, on the other hand, continue to be added to databases like UniParc at an exponential pace. We've seen what unsupervised learning can do for other sequence to sequence domains like text, and promising results from unsupervised learning of protein sequences. Combining deep predictive knowledge of protein sequences with advances like we've seen with AlphaFold is a promising and under-explored area of future research.

In this article we talked about the challenges inherent to the static folded protein problem of sequence-to-structure prediction, but there's also the dynamic protein folding problem, which is to understand the process of folding itself. Solving the former will give us vital insights into biology, actionable as improvements in biotechnology and medicine via better drug discovery and protein engineering. Solving the latter problem will add another order of difficulty as well as an order of benefit. Understanding the protein folding process will help us to understand why good proteins go bad, as they do in so many modern diseases such as those that cause dementia. This is also a very promising area for data-oriented researchers looking for a field full of unsolved problems where they can make substantial contributions with a real impact.

Other Deep Learning + Molecular Dynamics Blogs you may be interested in