What is Floating Point Precision?

Floating point precision is a method of representing numbers in binary format. Computers interpret numbers as binary sequences of 1s and 0s. We went over floating point Half Precision (FP16), Single Precision (FP32), and Double Precision (FP64) in a previous blog. This blog focuses on less common, lower-precision formats: FP8, FP6, and FP4 that are more geared towards neural networks and AI.

In floating point representation, the first binary digit indicates whether the number is positive or negative (the sign bit). The next group of digits forms the exponent, which uses base 2 to represent the magnitude of the number. The final group of digits is the mantissa (also called the significand), which represents the fractional part of the number. In these lower precision formats, the goal isn't to preserve mathematical accuracy but to save every little bit of compute, memory, and bandwidth all in favor of AI responsiveness and performance.

Why Lower Precision Exists

First, we should explain why floating precision became less precise. Modern neural networks are not limited by math — they are limited by data movement.

Moving weights and activations through memory costs far more time and energy than multiplying them. As models scale, especially large language models, performance becomes dominated by memory bandwidth, cache capacity, and power, not floating-point throughput. Lowering numerical precision is one of the most effective ways to relieve these bottlenecks.

This is why the industry moved from FP32 to FP16 and BF16 — and why that still wasn’t enough.

Reducing precision:

- Shrinks model size, improving cache locality

- Increases effective memory bandwidth

- Lowers energy per operation

- Enables higher compute utilization

AI neural network training can tolerate approximation. They are purposely trained with noise, optimized with stochastic methods, and evaluated on aggregate behavior rather than exact numerical correctness. Precision, therefore, becomes a budget to be spent carefully, not a fixed requirement.

Instead of “what precision should be used?” it became “where does precision matter?”

What is FP8?

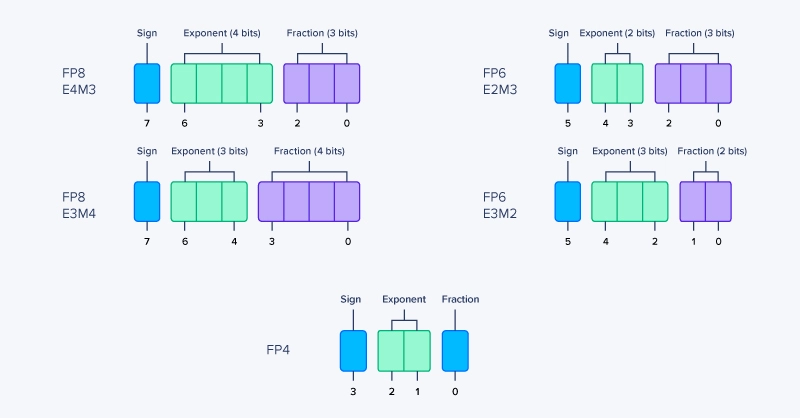

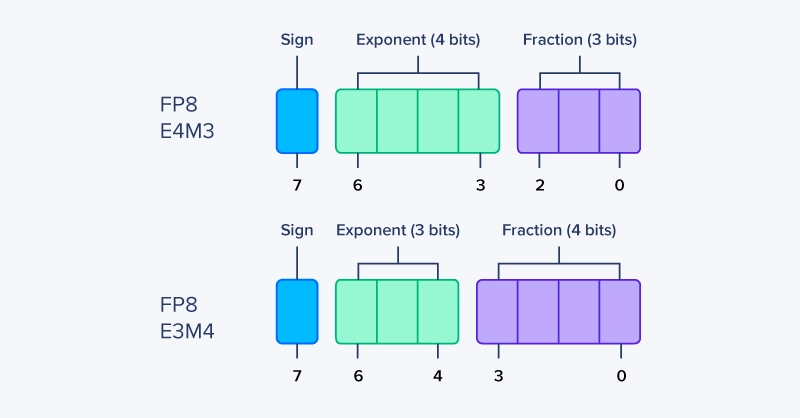

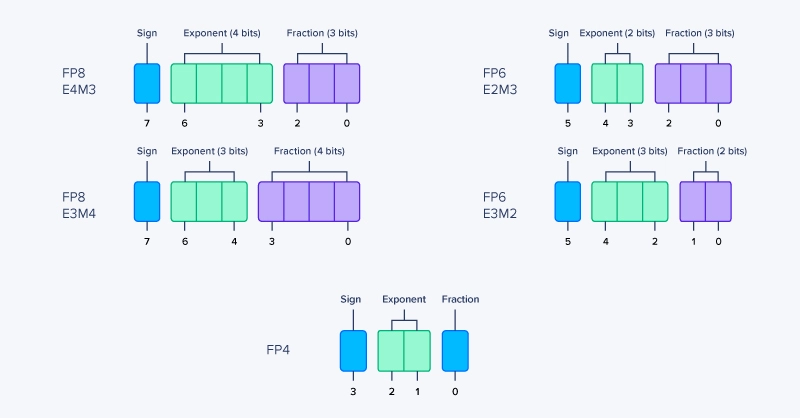

FP8 refers to a family of 8-bit floating-point formats, not a single standard. Like larger IEEE floating-point types, FP8 values has two versions: E4M3 and E5M2 (which make them quite self-explanatory).

At 8 bits, a single format cannot adequately cover both range and precision. Modern hardware and frameworks, therefore, mix FP8 variants:

- FP8 E4M3 is for instances where numerical precision matters more

- FP8 E5M2 is for instances where dynamic range is the limiting factor

In practice, FP8 values are rarely used in isolation. Computation is typically performed in FP8, while accumulation happens in FP16 or FP32, preserving stability despite the aggressive reduction in storage and compute precision.

FP8’s adoption in many AI accelerators is due to its ability fit into mixed-precision workloads.

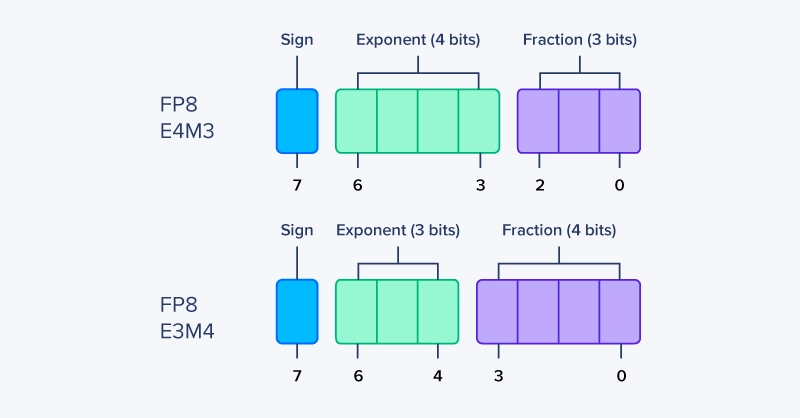

What is FP8 E4M3?

FP8 E4M3 prioritizes precision over range. With more mantissa bits, it represents values near zero more accurately, making it well-suited for activations and gradients with relatively tight distributions. It uses:

- 1 bit for positive/negative sign

- 4 bits for representing the exponent with base 2

- 3 bits for the mantissa/significand/fraction, i.e., value after the decimal point

What is FP8 E5M2?

FP8 E5M2 shifts bits from the mantissa to the exponent, increasing representable range at the cost of precision. This makes it more robust to outliers and large dynamic ranges, which are common in weights and intermediate results. It uses:

- 1 bit for positive/negative sign

- 5 bits for representing the exponent with base 2

- 2 bits for the mantissa/significand/fraction, i.e., value after the decimal point

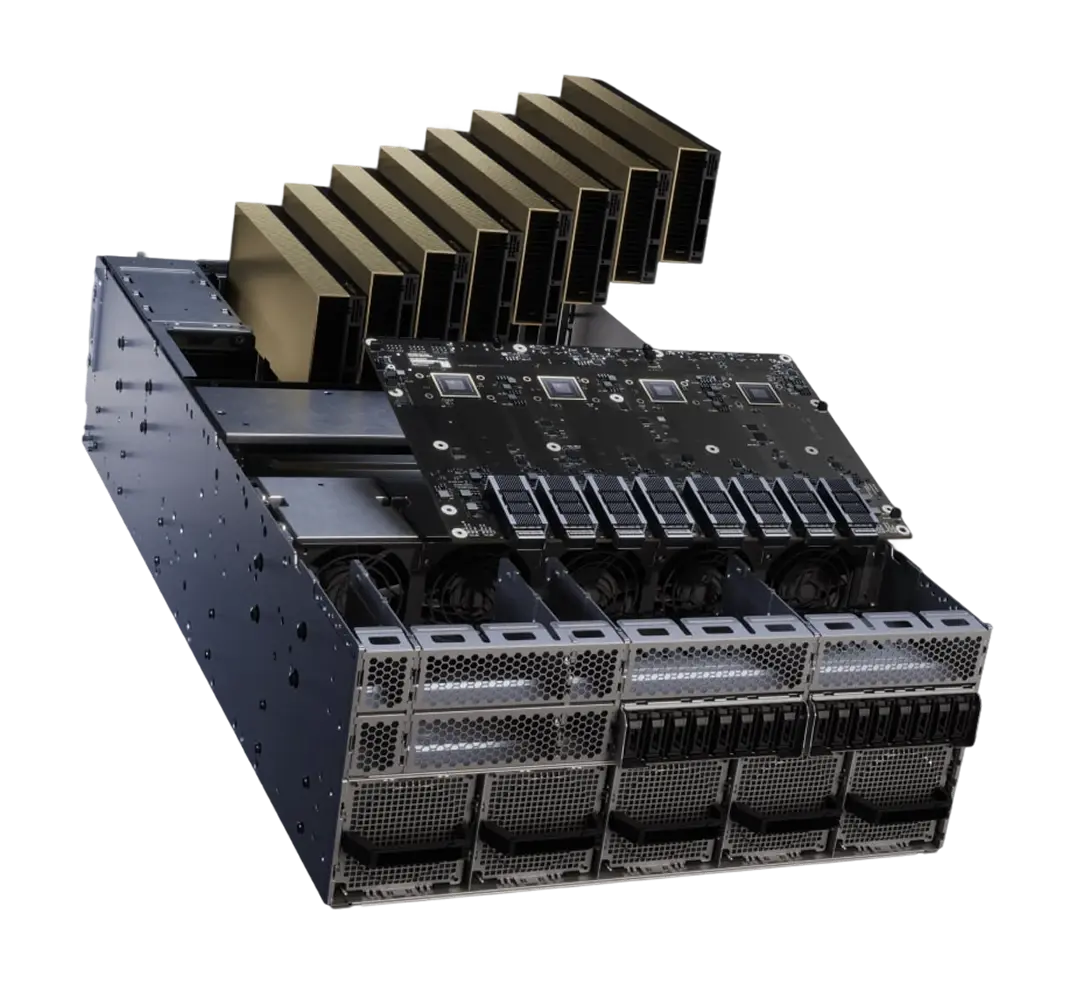

Accelerate AI & HPC with NVIDIA MGX

Empower your hardware with a purpose-built HPC platform validated by NVIDIA. NVIDIA MGX is a reference design platform by NVIDIA built to propel and accelerate your research in HPC and AI, built to extract the best performance out of NVIDIA hardware.

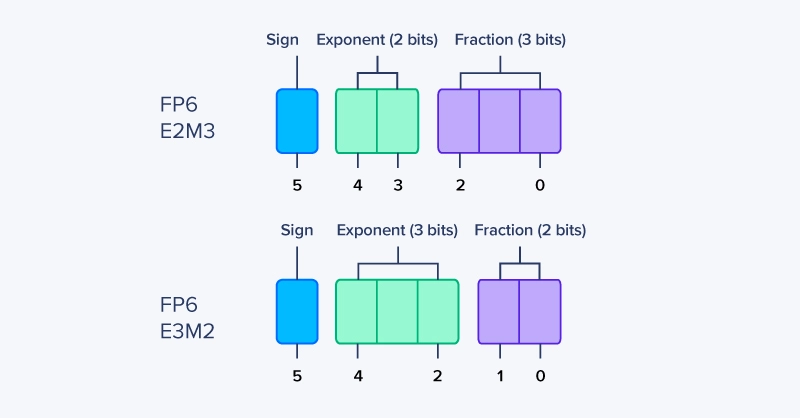

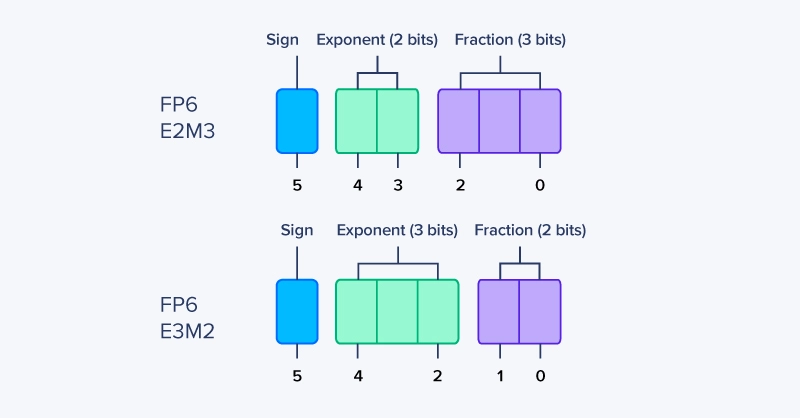

Get a Quote TodayWhat is FP6?

FP6 is not a single, standardized format, but a class of 6-bit floating-point representations. Like FP8, FP6 values are composed of a sign, exponent, and mantissa — but with only six total bits, the gains and tradeoffs are exaggerated.

While implementations vary, most FP6 proposals follow this general pattern:

- FP6 E2M3

- 1 bit for positive/negative sign

- 2 bits for representing the exponent with base 2

- 3 bits for the mantissa/significand/fraction, i.e., value after the decimal point

- FP6 E3M2

- 1 bit for positive/negative sign

- 3 bits for representing the exponent with base 2

- 2 bits for the mantissa/significand/fraction, i.e., value after the decimal point

Different exponent/mantissa splits target different use cases, but all FP6 formats suffer from extremely limited range or precision — often both. Unlike FP8, there is little room to balance range and precision within a single format. As a result, FP6 almost always requires aggressive scaling and careful value distribution control.

The efficiency gains over FP8 are modest, while the complexity cost is high. In many cases, FP8 captures most of the available performance and memory benefits without pushing numerical stability to the breaking point.

FP6 is primarily viable when:

- Value distributions are narrow and well-behaved

- Scaling is applied per-layer or per-tensor

- Accumulation happens in FP16 or FP32

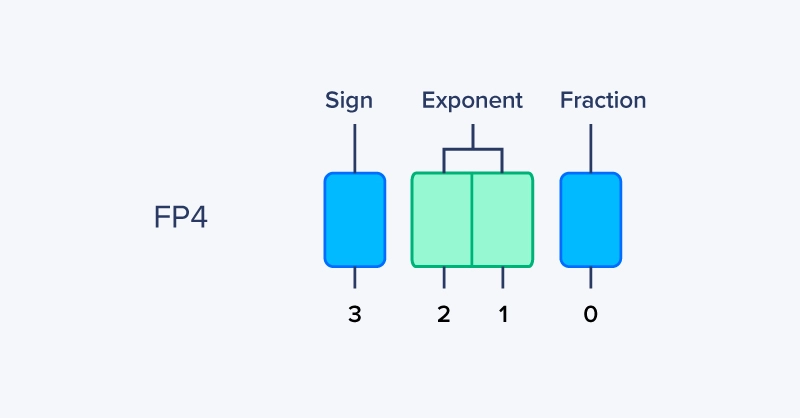

What is FP4?

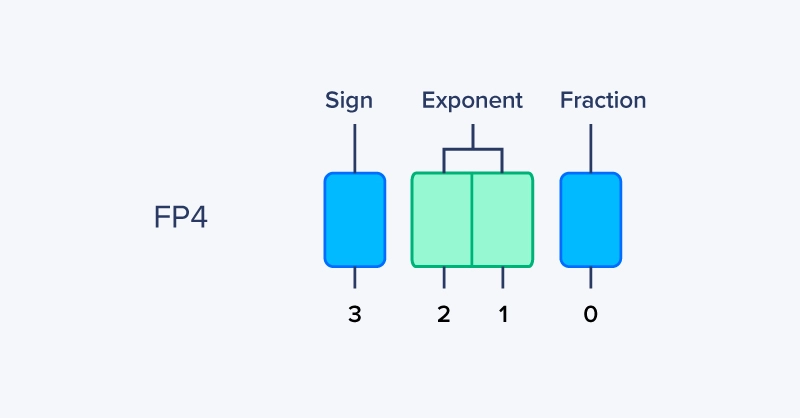

FP4 is the most aggressive floating-point format in practical discussion today. With only 4 total bits, FP4 pushes floating point to its absolute limits and exists almost entirely to satisfy hardware throughput and density goals. So far, only NVIDIA Blackwell Generation GPUs have native FP4 support.

There is no single FP4 standard, but typical designs use:

- Sign: 1 bit

- Exponent: 2 bits

- Mantissa: 1 bit

Some variants alter the exponent bias or remove special values entirely. Regardless of the exact layout, FP4 is extremely limited in range with almost no precision. FP4 is for maximizing Tensor Core throughput and minimizing memory bandwidth by enabling extremely high calculation density.

From a numerical perspective, FP4 is not intended to stand alone. It is a compute format, not a storage or accumulation format. When FP4 appears in hardware specifications:

- Values are typically scaled or block-scaled

- Computation occurs in FP4

- Accumulation happens in FP16 or FP32

- Inputs and outputs are often stored in higher precision

This mirrors the broader trend: ever-lower precision for compute, paired with higher precision where error accumulation matters.

As a result, FP4 is best viewed as a hardware capability, not a generally usable numerical format. Its inclusion in NVIDIA's GPU specifications signals where their GPUs push performance, not where most models can operate today. Reduced bit length during calculations result in less complexity and faster completion that compound over trillions of calculations a GPU has to make during AI training and inference.

Precision Placement Matters More Than Precision Size

Modern AI systems do not run at a single precision. They deliberately mix precisions across storage, compute, and accumulation, placing higher precision only where numerical error would otherwise compound.

This is why extremely low-precision formats are viable at all:

- Compute uses FP8, FP6, or even FP4 to maximize throughput

- Storage favors the smallest format that preserves accuracy

- Accumulation remains in FP16 or FP32 to maintain numerical stability

The effectiveness of a precision format depends less on its bit width and more on where it is used in the pipeline.

- FP8: Best general-purpose low-precision floating point. Used for training and inference compute with higher-precision accumulation

- FP6: Experimental and specialized. Viable only with tight scaling and controlled distributions

- FP4: Hardware-driven extreme. Used as a compute format under strict constraints, never in isolation

Lower precision is not about sacrificing correctness everywhere. It is about spending precision where it matters and reclaiming efficiency everywhere else.

FAQ about FP8, FP6, FP4

1. Why doesn’t lower precision completely break model accuracy?

Neural networks are inherently tolerant to noise. As long as accumulation and scaling are handled correctly, small numerical errors introduced during low-precision compute do not significantly affect final outputs.

2. Why are FP8 and FP6 floating point instead of using integers (INT8)?

Floating-point formats preserve dynamic range, which is critical for activations and gradients. Integer formats require explicit calibration and struggle with rapidly changing value distributions.

3. Why is accumulation almost always higher precision?

Errors compound during accumulation. Using FP16 or FP32 for accumulation prevents small rounding errors from dominating the result, even when inputs are extremely low precision.

4. Why isn’t FP4 widely used despite hardware support?

FP4 has extremely limited range and precision. Without strict scaling and tightly controlled distributions, numerical error grows too large for most models to tolerate.

5. How should I choose between FP8, FP6, and FP4?

Use FP8 for most low-precision compute, FP6 only for specialized or experimental setups, and treat FP4 as a hardware optimization rather than a general-purpose numerical format.

Conclusion

Low-precision floating-point formats shine wherever throughput, latency, or power dominate:

- Large Language Models (LLMs): FP8 is increasingly used for training and inference compute, while FP4 appears in tightly controlled inference kernels to maximize Tensor Core utilization.

- Data center inference: FP8 and INT8 reduce memory bandwidth and energy per token, directly improving cost and scalability.

- Robotics and autonomous systems: Lower-precision compute enables higher control-loop rates under strict power and thermal limits, especially on edge accelerators.

- Recommendation and ranking models: These models tolerate approximation well and benefit from aggressive precision reduction to meet latency targets.

- Scientific and industrial simulations with learned components: Surrogate models and learned solvers often run efficiently at FP8 without measurable degradation.

The common thread is not the application domain, but the constraint: when moving data costs more than computing on it, low-precision formats deliver outsized gains.

As hardware and software continue to co-evolve, the future of numerical formats will be defined less by IEEE standards and more by how effectively precision is spent.

We're Here to Deliver the Tools to Power Your Research

With access to the highest-performing hardware, Exxact offers customizable platforms for AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, and more. Every Exxact system is optimized for your deployment, budget, and desired performance so you can make an impact with your research!

Configure your Ideal GPU System for Life Science Research

Defining Low Precision Floating Point - What is FP8, FP6, FP4?

What is Floating Point Precision?

Floating point precision is a method of representing numbers in binary format. Computers interpret numbers as binary sequences of 1s and 0s. We went over floating point Half Precision (FP16), Single Precision (FP32), and Double Precision (FP64) in a previous blog. This blog focuses on less common, lower-precision formats: FP8, FP6, and FP4 that are more geared towards neural networks and AI.

In floating point representation, the first binary digit indicates whether the number is positive or negative (the sign bit). The next group of digits forms the exponent, which uses base 2 to represent the magnitude of the number. The final group of digits is the mantissa (also called the significand), which represents the fractional part of the number. In these lower precision formats, the goal isn't to preserve mathematical accuracy but to save every little bit of compute, memory, and bandwidth all in favor of AI responsiveness and performance.

Why Lower Precision Exists

First, we should explain why floating precision became less precise. Modern neural networks are not limited by math — they are limited by data movement.

Moving weights and activations through memory costs far more time and energy than multiplying them. As models scale, especially large language models, performance becomes dominated by memory bandwidth, cache capacity, and power, not floating-point throughput. Lowering numerical precision is one of the most effective ways to relieve these bottlenecks.

This is why the industry moved from FP32 to FP16 and BF16 — and why that still wasn’t enough.

Reducing precision:

- Shrinks model size, improving cache locality

- Increases effective memory bandwidth

- Lowers energy per operation

- Enables higher compute utilization

AI neural network training can tolerate approximation. They are purposely trained with noise, optimized with stochastic methods, and evaluated on aggregate behavior rather than exact numerical correctness. Precision, therefore, becomes a budget to be spent carefully, not a fixed requirement.

Instead of “what precision should be used?” it became “where does precision matter?”

What is FP8?

FP8 refers to a family of 8-bit floating-point formats, not a single standard. Like larger IEEE floating-point types, FP8 values has two versions: E4M3 and E5M2 (which make them quite self-explanatory).

At 8 bits, a single format cannot adequately cover both range and precision. Modern hardware and frameworks, therefore, mix FP8 variants:

- FP8 E4M3 is for instances where numerical precision matters more

- FP8 E5M2 is for instances where dynamic range is the limiting factor

In practice, FP8 values are rarely used in isolation. Computation is typically performed in FP8, while accumulation happens in FP16 or FP32, preserving stability despite the aggressive reduction in storage and compute precision.

FP8’s adoption in many AI accelerators is due to its ability fit into mixed-precision workloads.

What is FP8 E4M3?

FP8 E4M3 prioritizes precision over range. With more mantissa bits, it represents values near zero more accurately, making it well-suited for activations and gradients with relatively tight distributions. It uses:

- 1 bit for positive/negative sign

- 4 bits for representing the exponent with base 2

- 3 bits for the mantissa/significand/fraction, i.e., value after the decimal point

What is FP8 E5M2?

FP8 E5M2 shifts bits from the mantissa to the exponent, increasing representable range at the cost of precision. This makes it more robust to outliers and large dynamic ranges, which are common in weights and intermediate results. It uses:

- 1 bit for positive/negative sign

- 5 bits for representing the exponent with base 2

- 2 bits for the mantissa/significand/fraction, i.e., value after the decimal point

Accelerate AI & HPC with NVIDIA MGX

Empower your hardware with a purpose-built HPC platform validated by NVIDIA. NVIDIA MGX is a reference design platform by NVIDIA built to propel and accelerate your research in HPC and AI, built to extract the best performance out of NVIDIA hardware.

Get a Quote TodayWhat is FP6?

FP6 is not a single, standardized format, but a class of 6-bit floating-point representations. Like FP8, FP6 values are composed of a sign, exponent, and mantissa — but with only six total bits, the gains and tradeoffs are exaggerated.

While implementations vary, most FP6 proposals follow this general pattern:

- FP6 E2M3

- 1 bit for positive/negative sign

- 2 bits for representing the exponent with base 2

- 3 bits for the mantissa/significand/fraction, i.e., value after the decimal point

- FP6 E3M2

- 1 bit for positive/negative sign

- 3 bits for representing the exponent with base 2

- 2 bits for the mantissa/significand/fraction, i.e., value after the decimal point

Different exponent/mantissa splits target different use cases, but all FP6 formats suffer from extremely limited range or precision — often both. Unlike FP8, there is little room to balance range and precision within a single format. As a result, FP6 almost always requires aggressive scaling and careful value distribution control.

The efficiency gains over FP8 are modest, while the complexity cost is high. In many cases, FP8 captures most of the available performance and memory benefits without pushing numerical stability to the breaking point.

FP6 is primarily viable when:

- Value distributions are narrow and well-behaved

- Scaling is applied per-layer or per-tensor

- Accumulation happens in FP16 or FP32

What is FP4?

FP4 is the most aggressive floating-point format in practical discussion today. With only 4 total bits, FP4 pushes floating point to its absolute limits and exists almost entirely to satisfy hardware throughput and density goals. So far, only NVIDIA Blackwell Generation GPUs have native FP4 support.

There is no single FP4 standard, but typical designs use:

- Sign: 1 bit

- Exponent: 2 bits

- Mantissa: 1 bit

Some variants alter the exponent bias or remove special values entirely. Regardless of the exact layout, FP4 is extremely limited in range with almost no precision. FP4 is for maximizing Tensor Core throughput and minimizing memory bandwidth by enabling extremely high calculation density.

From a numerical perspective, FP4 is not intended to stand alone. It is a compute format, not a storage or accumulation format. When FP4 appears in hardware specifications:

- Values are typically scaled or block-scaled

- Computation occurs in FP4

- Accumulation happens in FP16 or FP32

- Inputs and outputs are often stored in higher precision

This mirrors the broader trend: ever-lower precision for compute, paired with higher precision where error accumulation matters.

As a result, FP4 is best viewed as a hardware capability, not a generally usable numerical format. Its inclusion in NVIDIA's GPU specifications signals where their GPUs push performance, not where most models can operate today. Reduced bit length during calculations result in less complexity and faster completion that compound over trillions of calculations a GPU has to make during AI training and inference.

Precision Placement Matters More Than Precision Size

Modern AI systems do not run at a single precision. They deliberately mix precisions across storage, compute, and accumulation, placing higher precision only where numerical error would otherwise compound.

This is why extremely low-precision formats are viable at all:

- Compute uses FP8, FP6, or even FP4 to maximize throughput

- Storage favors the smallest format that preserves accuracy

- Accumulation remains in FP16 or FP32 to maintain numerical stability

The effectiveness of a precision format depends less on its bit width and more on where it is used in the pipeline.

- FP8: Best general-purpose low-precision floating point. Used for training and inference compute with higher-precision accumulation

- FP6: Experimental and specialized. Viable only with tight scaling and controlled distributions

- FP4: Hardware-driven extreme. Used as a compute format under strict constraints, never in isolation

Lower precision is not about sacrificing correctness everywhere. It is about spending precision where it matters and reclaiming efficiency everywhere else.

FAQ about FP8, FP6, FP4

1. Why doesn’t lower precision completely break model accuracy?

Neural networks are inherently tolerant to noise. As long as accumulation and scaling are handled correctly, small numerical errors introduced during low-precision compute do not significantly affect final outputs.

2. Why are FP8 and FP6 floating point instead of using integers (INT8)?

Floating-point formats preserve dynamic range, which is critical for activations and gradients. Integer formats require explicit calibration and struggle with rapidly changing value distributions.

3. Why is accumulation almost always higher precision?

Errors compound during accumulation. Using FP16 or FP32 for accumulation prevents small rounding errors from dominating the result, even when inputs are extremely low precision.

4. Why isn’t FP4 widely used despite hardware support?

FP4 has extremely limited range and precision. Without strict scaling and tightly controlled distributions, numerical error grows too large for most models to tolerate.

5. How should I choose between FP8, FP6, and FP4?

Use FP8 for most low-precision compute, FP6 only for specialized or experimental setups, and treat FP4 as a hardware optimization rather than a general-purpose numerical format.

Conclusion

Low-precision floating-point formats shine wherever throughput, latency, or power dominate:

- Large Language Models (LLMs): FP8 is increasingly used for training and inference compute, while FP4 appears in tightly controlled inference kernels to maximize Tensor Core utilization.

- Data center inference: FP8 and INT8 reduce memory bandwidth and energy per token, directly improving cost and scalability.

- Robotics and autonomous systems: Lower-precision compute enables higher control-loop rates under strict power and thermal limits, especially on edge accelerators.

- Recommendation and ranking models: These models tolerate approximation well and benefit from aggressive precision reduction to meet latency targets.

- Scientific and industrial simulations with learned components: Surrogate models and learned solvers often run efficiently at FP8 without measurable degradation.

The common thread is not the application domain, but the constraint: when moving data costs more than computing on it, low-precision formats deliver outsized gains.

As hardware and software continue to co-evolve, the future of numerical formats will be defined less by IEEE standards and more by how effectively precision is spent.

We're Here to Deliver the Tools to Power Your Research

With access to the highest-performing hardware, Exxact offers customizable platforms for AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, and more. Every Exxact system is optimized for your deployment, budget, and desired performance so you can make an impact with your research!

Configure your Ideal GPU System for Life Science Research

.jpg?format=webp)